When Gods Walk Among Us: A Story of Faith, Family & New Beginnings

A Tale of 'Household Gods' + Special New Year's Book Sale 🕯️

A very merry Friday Scribblers,

I hope you all had a special Christmas week, whatever that does or doesn’t mean to you, and that you had time to cuddle up with a good book! We can certainly help with that - scroll to the bottom of this email to see a sale coupon.

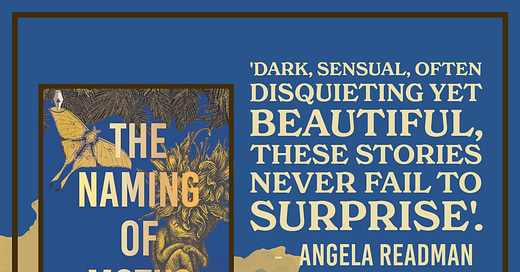

Today I’m sharing a hopeful short story with you, from Tracy Fells’ empathy-rich short story collection ‘The Naming of Moths’. The collection focuses on feminist mythology, motherhood and magic. This story falls into the ‘Magic’ category, but also looks at connection, the strength that can be found in faith and the joy and hope of new life.

HOUSEHOLD GODS

Mohammed placed the cube of lamb into the ceramic dish, its minty aroma mingling with the hint of cranberry and cinnamon from the lighted candle. He’d bought a range of Christmas-spiced tea lights in the January sales, which would help to keep Vesta’s flame alight. When he had to leave the house, Mo blew it out, not trusting Vesta’s naked flame alone with his mother.

Into the second dish he poured a libation of elderflower cordial. “Accept my offerings, Janus, and help to ease the ending I face today,” he whispered, eyes open and fixed on the homemade shrine. Typically he sought Vesta’s blessing, as protector of the home and family, before leaving the house, but Mo felt that the sad and difficult day ahead required additional support. He repeated the request six more times under his breath.

Later he would bring cake for his household gods. He was a good son, but a poor Muslim, and had promised his mother he would bring home a cake: Victoria sponge, with real jam, her favourite, to celebrate the prophet’s birthday. Today he would also visit the hospital to see the baby for the first, and possibly last, time; born on the first day of the year and now twenty-four days old. Not a day for celebrations.

Despite not eating meat since he was nine years old, the same age he’d discovered his true faith, Mo wrinkled his nose approvingly at the tempting smell of the minted lamb. After finishing his morning shift at Meadowbank garden centre Mo had chopped and spoon-fed the rest of the steak, along with garlic mash and home grown petis pois, to Mummy. He liked to see her eat a good lunch before he set off for the library. Friday afternoons, his one afternoon off, were for study and the world wide web was his undisputed god of research. He didn’t own a computer; at two o’clock each Friday he would take his place at one of the public terminals in the town’s library.

The telephone call, coming as Mo helped his mother waddle back from the commode, exploded his afternoon plans. Mo checked his pulse, ninety-eight and rising, but could not ignore the clipped vowels of the duty nurse who instructed him to come immediately and say goodbye to his daughter.

Extinguishing Vesta’s flame, he bowed towards the shrine, eyes closed, to murmur a final prayer. He kept the shrine in his bedroom so as not to upset Mummy. Mo had created his design from photographs he’d found on the Internet of a typical Roman household shrine. The finished relief appeared authentic with its weathered (cold coffee worked a treat) columns and sloping roof chiselled from modelling plaster. First tracing with heavy pencil the dancing figures and the writhing snake, Mo later coloured in the sketches using a tin of watercolour paints he found in an attic crate of his old toys and books. Balanced on the apex of the shrine was a stone statue, with two faces, both adorned with long curling beards. The god Janus, protector of doors and gateways, was often represented by two heads to signify how he could simultaneously watch both the past and the future. Mo didn’t envy the god this talent: he could barely think about the past let alone face the future.

If Mo had made an offering to give thanks for the baby’s birth then maybe he wouldn’t now have to make the torturous visit to her hospital incubator – to stand with Aisha and pretend to grieve for another man’s child.

Mo selected a TV channel showing an afternoon of black and white films, tucked the blanket of crocheted squares around his mother’s legs, and kissed her dry forehead.

“I have to go out, Mummy,” he said clearly to her blank face, “I will ask Mrs Harris to pop in later and make you more tea. You like your afternoon tea, don’t you, Mummy?”

She blinked, as if in acknowledgement, but her dark eyes looked past him. Pulling the curtains across to keep the heat in, Mo flicked the light switch on and off seven times before crossing the threshold. He quietly closed the door to his mother’s sitting room and repeated the action with the kitchen, downstairs cloakroom and hall lights. The front door was safely chained and double-locked, so he let himself out through the kitchen door. He locked and unlocked the door six times and then, after a quick prayer invoking the blessing of Janus, he locked it one final time.

Mo dropped the key into Mrs Harris’ shaking hand, being careful not to brush against her fingers.

“Yes, dear,” she chirped, “I know how Mrs Khan likes her tea. I’ll look in on her after the three o’clock at Chepstow. Now she won’t need the loo or anything, will she?”

He shook his head. Mo was below average height, but he still looked down at his neighbour, the tight white curls of her perm hugging her scalp in the snapping easterly wind.

“She went after lunch,” he said starting to back away from the old lady.

“Oh, that’s lovely, dear.” There was a splash of lipstick on a lower tooth and the cherry-red hadn’t made it all the way round her cracked lips. “Your mother is rather a big-boned lady.”

With older women, particularly white English ladies, Mo always felt the need to end an interaction with a slight bow. He did this now to hide the twitch of a smile. He knew Mrs Khan’s bones were no bigger than any other Pakistani woman of her age, but they were significantly well insulated.

Mrs Harris stretched out her arm, almost as if she were about to stroke his head, but then pulled it back to her chest. “God be with you,” she whispered and then scuffled back inside her house.

Which god, thought Mo, when there were so many to choose from? Two days after his ninth birthday Mohammed had woken to find Uncle Osman, nicknamed Oz, squatting at the edge of his bed, tears rolling down his shiny cheeks. Usually he had the smiling appearance of a garden Buddha, but that night Uncle Oz sagged like a deflating rubber ring. He gurgled and spluttered and finally spat out a story involving a lorry, a moped and Mo’s father’s delivery van. There was no happy ending to the bedtime tale. Mo buried the details of his uncle’s words and accepted that his father was gone. He had left them for good. Uncle Oz told Mo he had to pray to God, pray for his father. But what was the point of prayers for a dead man?

At nine years old Mo had decided one god wasn’t enough. If you were to protect and keep safe all those you loved, then you needed a whole battalion. Multiple prayers to multiple deities distributed your fielders across a dangerous pitch. At least one of them should always be there, in place to take that fateful catch. The Romans hedged all their bets by spreading their wishes and prayers across a multitude of gods. Mo adopted their beliefs because it was the perfect religious contingency, removing risk and misery from his fragile existence.

He also reasoned that his father, when leaving the safety and sanctuary of the family home, had left himself open to the fates. Crossing the threshold from inside to out was a dangerous undertaking. By his tenth birthday Mo had developed numerous strategies to cope with the challenge of endless doorways.

Mo continued with his beliefs and little rituals that had begun after his father’s death. However, according to Uncle Oz, a single man over thirty needed a wife. After Mummy’s second, and more debilitating, stroke Mo could no longer cope with her alone and continue to work at the garden centre. Several carer visits were scheduled each day to help bathe and feed Mrs Khan while Mo was working. Uncle Oz reasoned a wife would be a more permanent solution – and cheaper.

Uncle Oz took care of all the arrangements and Aisha was shipped to Sussex. She came from a good family, known to his uncle, and brought with her one small suitcase of clothes. Mo’s new wife spoke no English and, after five months, living in the provincial suburbs had made little progress with her vocabulary. With Uncle Oz she’d spoken only Urdu. To Mo she said little more than, “Good morning, husband” and “Good night, husband”, recited and learned from Uncle Oz. After the wedding Mo moved to the spare bedroom and painted Aisha’s room a pale lemon, a colour chosen to complement her favourite sari.

Mo always made an effort to tell his mother about his day at Meadowbank nursery. Talking to her was excellent therapy, or so he’d been told. She did not respond.

One evening, after an unexpected late shift at Meadowbank, Mo arrived home to find Aisha sitting with his mother. He watched the two women from beyond the kitchen door as Aisha spoon-fed his mother from a bowl of soup, chatting happily away in Urdu about her life before England. Aisha talked of her younger brothers and sisters and their silly pranks. She was funny. Her eyes were bright, her smile relaxed. Her long ebony hair, usually tightly pinned in a coil at the back of her head, hung loose across both shoulders. Mo crept up to his bedroom, leaving his wife undisturbed by his return.

Now Aisha was at the hospital, where she visited every day since the birth. Mo would be a dutiful husband and take his place at her side.

After reversing the car from the garage Mo parked on the drive and returned to the house. He tugged on the front door and then the kitchen door; they were both secure, finally murmuring some words of thanks to Vesta he climbed back into the grey hatchback.

***

Mo spoke his name clearly into the box on the wall. A buzzer trilled and the glass-fronted door clicked open. Inside the Special Care Unit a middle-aged nurse, wearing pristine white, escorted him to a corner room suffused with light. Winding an elastic band in her fingers the nurse pulled her blond hair into a ponytail, instantly making her look ten years younger. Turning on her heels, the ponytail almost slapping his face, the nurse strode off again, leaving Mo alone outside the door.

Mo peered through the round window, unsure if he could enter without an escort. Six incubators sat inside like elevated greenhouse trays. Three of them were watched over by electronic displays and hushed couples. By the fourth sat Aisha, her hands held in the lap of her sari, her head bowed.

“Mr Khan?” A sharp, female voice came from behind him. Another nurse, this one wore a navy-blue uniform, squinted at him with dark, narrow eyes.

“Yes,” he answered backing up against the door, “but please call me Mo.”

“Your English is excellent, Mr Khan. I’m surprised because your wife can hardly speak a word. Thankfully, one of the ward porters speaks Urdu and he’s translated anything we needed to know from her.” Her tone was scolding.

Mo wanted to counter, gently state he was as English as the next man, born in Brighton General and living in Sussex all his life, but the next man, jogging past in a flapping white coat, called out with an antipodean accent for someone to hold the main door. Instead, Mo replied, “My wife has only lived here for a short time.”

One silver-grey eyebrow twitched as the older nurse sucked on her lip. “Your wife’s vigil, Mr Khan, has been lonely. But you’re here now and your company will ease the waiting.”

He followed the blue nurse into the incubator room. The rhythmic sigh of oxygen pumps and the infrequent beep of some machine were the only background sounds. Aisha stood as her husband approached. Her gaze flicked from him to settle again on the baby lying beneath a Perspex roof.

The nurse spoke behind him. “A prem baby is particularly susceptible to infections, Mr Khan, we’ve treated the pneumonia as best we can but now it’s–”

“–In the lap of the gods?” said Mo quietly.

“Simply down to the strength of your daughter’s immune system,” she finished.

He didn’t see her leave, but the starched blue nurse was replaced by the smiling nurse in white, who stood so close Mo could smell antiseptic and cigarette smoke on her skin. She squeezed his hand.

In the men’s toilets Mo lathered his hands and wrists with soap, then rinsed them in the tepid water. Five times would be sufficient, he thought, but returned to the sink to wash twice more.

Walking back to the incubator room Mo passed the open kitchen area where the navy-blue nurse stood, her back towards him, talking with a male colleague. “Poor mare, shipped over here and nobody cares enough to give her the tools to survive.” Her voice carried above the stirring teaspoon of her colleague. “Told Jamal she was in love, that she had a boyfriend back in Pakistan – a medical student. But his family didn’t approve or something and she was the one that had to leave. I feel sorry for her, dumped with a bloke she’s never met and expected to start spitting out babies like chapattis.”

The male nurse inclined his head towards Mo and the woman slowly twisted round to stare at him. She sipped at the mug in her hands, but didn’t offer an apology.

He could leave now; drive home and get on with dinner. Mummy needed to eat before the temporary carer arrived to bathe her before bedtime. His duty at the hospital had been executed, he’d seen the baby as requested – what more was there for him to do? Aisha wasn’t going anywhere, so his presence was irrelevant.

The smiling nurse held open the door to the incubator room and gestured to Mo, “Are you coming back in, Mo?”

A strand of blond hair had slipped free to dangle across her cheek. Mo needed to see her push it back into place, but she kept the door open with her backside unaware of her unbalanced hair.

“No,” he said, deciding quickly, “not yet.”

Something flashed in her blue eyes, like the reflected glint of a flame. She was beautiful, Mo realised, quite beautiful. “A child is always a blessing,” she said. A frown creased her forehead, yet the words were tender and soothed him.

Beyond the sliding doors of the main reception Mo turned his mobile back on. A man in a striped dressing gown leant against a pillar taking long drags from a cigarette; his other hand supported the stand of his drip with the tube still attached, disappearing up his sleeve. The sky looked tired, drained of light. Clouds hung low, grey and brooding, swollen with the promise of snow.

***

The baby was another man’s child. Mo was certain on the paternity of Aisha’s daughter because of two things. Firstly, his new wife had landed at Heathrow already three months pregnant, Uncle Oz confessed this before her arrival and secondly, he had never slept in her bed. Mo lost his virginity during his teenage bacchanalian phase, a time of experimentation and too much vodka. Alison, with hair the colour of copper piping, let him do it at the end of school party in her parent’s room. He was sixteen and had already starting working at the garden centre. There were, occasionally, other girls after Alison but Mo had not yet consummated his marriage with Aisha. She was a stranger to him. After Mummy’s first stroke, his affliction had worsened to the point where Mo could barely tolerate the touch of another human being.

The man with the drip raised his eyebrows and nodded, tossing Mo a silent alright mate. Mo turned away to stare across the car park where an ambulance was backing towards the doors of A and E.

“Mrs Harris?” he spoke into his mobile. He turned up the volume to hear the old lady’s whispery voice. “Oh, good, I’m glad Mrs Khan enjoyed her afternoon tea. Could I possibly ask another favour, Mrs Harris?” Snow was falling now. “Yes, I will be here for some hours. If you could sit with…” Drip man stubbed his cigarette against the concrete pillar and let it fall. Specks of snow began to settle on the tarmac. “Mummy, Mrs Khan, loves soup – thank you. Yes, I will let my wife know you are praying for our daughter.”

A child is always a blessing.

Mo shut down the phone. How did Mrs Harris know the baby was a girl? He’d never talked about Aisha’s baby with Mrs Harris. Had Aisha learned more English than he realised?

His right hand was shaking. Mo hadn’t changed out of his work clothes, so still wore the green uniform of the garden centre: drill trousers, polo shirt, sweatshirt and the ivy-green fleece with Meadowbank’s red and gold logo. It was the cold of course; he was bound to shiver, standing inert outside in a snowstorm. As the doors slid open Mo saw himself in the glass, a short brown man in shabby green. His father had been lost for twenty-five years, but was now returned to them. Mo saw him all the time, whenever he faced his own reflection. The same receding hairline, the swelling bald spot racing to meet his forehead, and the same fearful eyes were all part of the inheritance. He held a finger under his nose. All he needed was a neatly-trimmed moustache and his father would be fully resurrected.

Did Janus watch over sliding doors? As the god of doorways he must lurk nearby, never dropping his guard no matter who entered.

Drip man shuffled past. “The gods walk amongst us,” said the man, staring straight ahead. From the back his thick neck bulged, prickled with stubble, almost like a second chin.

“Excuse me, what did you say?”

The man stopped, turning to blink at Mo. “Sorry, mate, didn’t say nothing.”

“My mistake,” said Mo.

***

Aisha had been crying. A paper towel lay scrunched in her lap and dark lines creased her eyelids. The incubator was open and for the first time Mo peered into the baby’s self-contained world. A nappy hung off the baby’s bony hips. From her nose protruded a plastic tube, taped across her tummy. She wore one pink, hand knitted mitten, on her right hand. The other was bare and the fingers twitched in time with the rise and fall of her chest.

“You can hold her hand if you wish.” The nurse in white was once again at Mo’s side. He glanced at her and she nodded. “There’s little she can catch from you that will do any more harm than pneumococcus.”

Before he could prepare himself the baby’s hand curled around his finger. Her grip was surprisingly strong. His breathing raced to match his heartbeat, but he was determined not to pull away from her touch. Mo gazed at the creases on her coffee skin, the baby’s hand looked like his own, a perfect replica, but in miniature.

“Why is she wearing a mitten?” said Mo.

“To stop her pulling out the tube. Aisha expresses her milk and we feed baby through the tube, it goes straight into her stomach. She is a bit small, and weak, to feed by mouth.”

“But why only one mitten?”

Her expression softened. “Somehow she lost the other one before you came in. We can’t find it anywhere.”

Mo recalled the telephone message he’d picked up earlier. The navy-blue nurse was called Julia, now he remembered. “Julia told me she may not last the night, that she is very weak.”

“So many of them try to grow wings, but I believe your little girl wants to stay. Do you have a name for her?”

Would a name anchor her? Weigh down her wings? A nagging voice whispered inside his head, his mother’s voice. She cannot meet God without a name.

Another voice spoke to him, Aisha’s quiet voice. “Nadira.”

“Nadira, after my mother?”

Aisha nodded.

“This baby is a rare and precious gift; let her bring love into your home.” The nurse’s words unfurled around them like an embrace. Mo looked away from Aisha, but the pony-tailed woman had already slipped away. Mo didn’t know the nurse’s name, as she hadn’t worn a nametag. She didn’t return to say goodbye at the end of her shift and he never saw her again in the unit.

“You’ve been very helpful to Mummy,” Mo said in Urdu to Aisha.

“I wish I’d known her before the stroke. I think we would have become friends.”

Mo hesitated, swallowing several times. “I think she likes you very much.” He thought of how Aisha read to her every day, of how she fed Mummy, waiting patiently for each mouthful to go down before gently offering another.

A hint of a smile crept onto Aisha’s face. Her black eyes met his briefly then swept back to the baby. She wasn’t conventionally pretty, her face a little too thin and pointed, but her eyes were kind. “I think she has a good son,” said Aisha softly. “A kind and loving son.”

He thought of what he’d overheard outside the nurse’s kitchen. “You don’t have to stay. You could go home… after.” Mo stopped. There were no appropriate words to frame his meaning.

Aisha shook her head and replied carefully in English. “I want to stay.” She reached forward to stroke her baby’s chest and began to talk again in Urdu. “This is our home now. We will stay if you wish us to. I will ask nothing more of you.”

Together they stood beside the incubator, watching over Nadira.

Snowflakes funnelled towards the windows like desperate white moths. The ticking machines and wheezing babies settled to a low, constant hum, as Mo began to recite his prayer. He didn’t care which of the gods heard it – he knew they were all listening. Nadira snuffled like a kitten in her incubator, pawing at the feeding tube with her mittened hand, still tightly holding onto Mo’s finger with the other.

***

At dawn, Mo drove Aisha home. Overnight the snow had blown away and the roads were clear. They both planned to bathe and eat, before returning to the hospital to continue the vigil at their daughter’s side. The budding wings had faded with the snow as the antibiotics finally kicked in. Baby Nadira was staying for now.

Mummy was lying on her back and a rattling snore told Mo she was still sleeping. Mrs Harris had spent the night, squashing in beside Mrs Khan to teeter at the edge of the counterpane. The old lady was also asleep; the white curls around her ear were stuck flat against the pillow and her face.

He returned to his own bedroom. It was time to give thanks to the household gods.

Someone had beaten him to it. Vesta’s flame was alive and flickering before Mo’s plaster shrine. He had extinguished the candle, and checked it seven times before leaving for the hospital, but now the candle was burning in its dish. Beside it lay a single pink woollen mitten.

You can read more stories from ‘The Naming of Moths’ here in paperback and here in Kindle.

Now for our promised festive sale! We adore putting together our curated anthologies and below you’ll find a selection of our charity books, such as gorgeous hardback A4 colour coffee table book ‘Planet in Peril’ and our powerful protest colour anthology ‘Demos Rising’, alongside curated short story collections such as ‘Modern Gothic’ and ‘The Ones Who Flew The Nest’. We are now back to shipping after Christmas! The below sales discounts end on the 31st of December at midnight.

15% off Free Subscriber discount on anthologies: Anthologies15

30% off Paid Subscriber discount on anthologies:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Publisher with a Conscience: Fly on the Wall Press to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.