The psychology of living under oppressive regimes

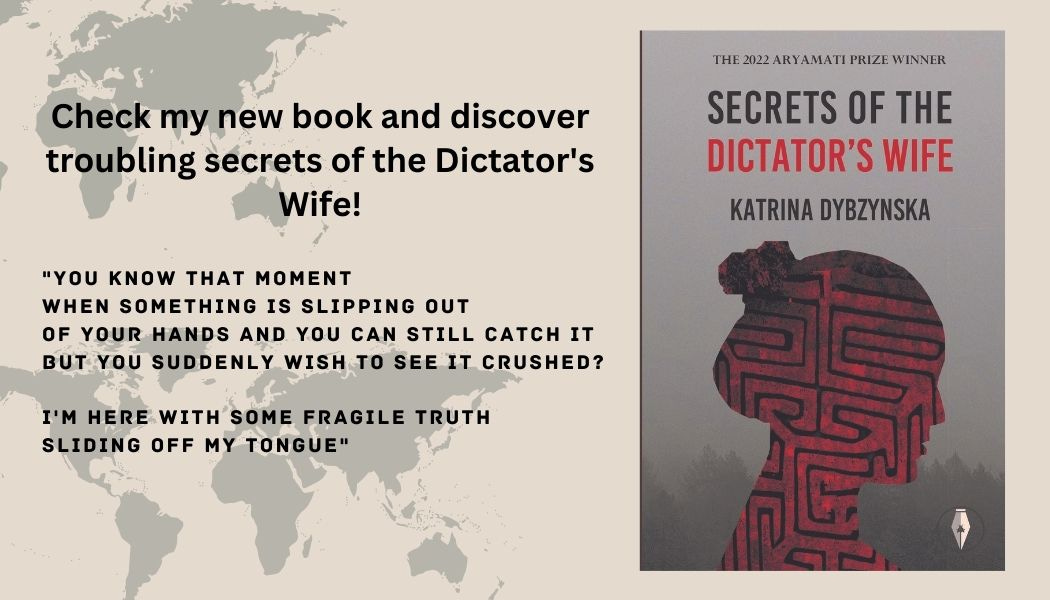

An interview with poet Katrina Dybzynska, author of ‘Secrets of the Dictator’s Wife’ and pre-orders for Ricky Ray's 'The Soul We Share'

Happy Friday Scribblers,

I hope you are having a gorgeous day. Today we’re focusing on our in house Aryamati Poetry Prize, with an interview with the 2022 winner, Katrina Dybzynska, author of ‘Secrets of the Dictator’s Wife’. We delve into the themes of power dynamics and compliance, exploring the psychology of living under oppressive regimes and the role of imagery and symbolism in conveying these themes. We also chat about the ongoing struggle against authoritarianism, the multi-layered interpretations of poetry by readers, and Kat’s future projects centered around power struggles and personal themes such as grief and connection to place.

Very excitingly, we have just launched preorders for our 2023 Collection Winner: Ricky Ray and ‘The Soul We Share’. The first 100 pre-orders will arrive with a pressed autumn leaf and a limited-edition postcard artwork of Addie. 17% of each sale will be donated to the Irish Setter rescue organization (Irishrescue.org)

‘There’s something about being alive /

that makes us cry out for help.’

Through visceral and vulnerable poetry, Ricky Ray meditates on the pain and powerlessness that comes with an awareness of our mortality. Finding joy through connecting with the natural world, Ricky navigates his ache of living. Allowing us to accompany him and his beloved service dog, Addie, through the scenic woodlands of Kansas, Illinois and Connecticut, the lines between humans, animals and nature blur.

“These are poems of true immersion in the belief of the earth as Gaia, whilst at the same time making known and felt the author’s painful and disabling condition, his everyday life and his hopes for the future. Unlike any other collection I have come across” - Dr Maura Dooley

Now let us chat to Kat!

Blurb: Behind the gilded cage of dictatorship lies The Dictator's Wife. Her world - one of secrecy, complicity and fading love filtered through gossamer lines that blur right from wrong. In this revealing collection, award-winning poet Katrina Dybzynska draws back the curtain on the unnamed wife of an enigmatic dictator. Her inner monologue builds an intoxicating picture of mystery and isolation where even champagne flutes crack under pressure.

1. What inspired you to write from the perspective of a dictator's wife? What themes were you looking to explore?

Secrets of the Dictator’s Wife is a book about the dynamics of power and the thin line of compliance. I was very curious about the tipping points – I wanted to know if there was some limit of endurance that, when crossed, changes history. I often wonder about what happens behind the stage of revolutions. Why do societies put up with a regime for decades and then one day, people grab their weapons? And how is that different from those in abusive relationships who on a seemingly uneventful Tuesday, after countless ignored red flags, just walk away? The character of the Dictator’s Wife offered a great insight into both of those mechanisms, so she became my point of reference. Initially, I explored her as a persona in a single poem. I had not planned to follow her perspective throughout the whole pamphlet, but I just could not get her out of my head. She kept appearing in the pieces I wrote afterward until I had to give in to her taking over the book.

2. Many of the poems give insight into the complex psychology of someone living under an oppressive regime. What kind of research did you do into this mentality?

I read anything I could get my hands on, although it would have to be often about the toolboxes of dictators rather than their subjects’ mentality. Certainly, I did not come across much information on women married to such figures that would go deeper than anecdotes on the number of shoes they owned or brands of clothes they favoured.

When it comes to shaping the mentality of a society that would seek a ruthless ruler, I found out that it is a gradual process in which the subjects get slowly implicated until the lines between the accuser and the accused are blurred. Very few in such a system can claim that their hands are clean. We tend to think that if we found ourselves in times of the Second World War or other trying circumstances, we would no doubt be on the right side of history. But Polish poet, Wislawa Szymborska, reminds us, “We know ourselves only as far as we have been tested.” And maybe even that is an optimistic view because we are not consistent beings and could, upon retaking the exam, reach our breaking point.

I also did a lot of research on those in violent relationships because I needed to know how the individual and the collective speak to each other.

3. The imagery throughout is very vivid, like the painting metaphors and the garden weeds. How do you go about crafting these visual elements into your writing?

I am glad that it felt that way because I think that it is the powerful imagery that often remains in the reader’s mind long after that perfectly crafted metaphor evaporates. I was aware that with the focus of this book being on concepts of power and obedience, it could easily become very abstract and I hoped to balance it out with something more tangible.

But the elements you mentioned play a much more vital role than simply being anchors. I wanted to imagine what could serve as a wake-up call for someone who has all the incentives to turn a blind eye to the atrocities committed by the system she is an integral part of. And I strongly believe that both arts and wilderness have the power to do that.

The Dictator’s Wife studies weeds for their resistance, resilience, and adaptability. These plants represent for me the whole ecosystem that we have forgotten how to be in relation with and I am convinced that is at the roots of many problems we currently face, including authoritarian governments.

4. There are references to fairy tales and mythological figures. What purpose did borrowing from these stories serve for this collection?

Like art and the untamed I was just referring to, fairy tales and myth, have the capability of reminding us of something bigger we belong to. They can be medicinal in their power of confronting you with the mirror, sometimes in the least expected moment of the story. Perhaps, you would rather see yourself as a princess but suddenly, you resonate much more with a dragon. Especially in censorship, these tales become an element of the struggle that should not be underestimated; the ground where everything that cannot be said directly takes place, so it felt fitting to include them in this collection.

In the poem you are referring to, The Dictator’s Wife’s Turning Point, I was also drawn to the contrast between this domesticated, intimate scene of the Dictator’s Wife reading a bedtime story to her kids and the whole avalanche of challenging questions that it provokes in her. This scenario is also consistent with what I discovered during my research – it is not necessarily the most dramatic event that turns the tables but a tiny drop that wears away a stone. Something mundane, that happened many times previously and caused no reaction and then suddenly hits the right note.

5. Silence and disappearance are common motifs. What do you think these represent for the speaker?

A big part of authoritarian systems is the erasure of the elements in the culture where the resistance could stem from and the silencing of the opposing voices. This delicate dance of what can be said and second-guessing every word is the reality I strove to capture.

What also interests me is how that speaks to the lost importance of the language. We used to believe in spells and curses, where a single word could literally decide about life and death. Some of that fear seems to be preserved in the insistence of dictators on the imposed narrative.

This silencing and erasure are clear as well in the fact that we never learn the Dictator’s Wife’s name. But that is not unusual. Naming is the tool of power - while being anonymous can suggest disposability, being named is to be framed and owned.

6. The ending poem leaves things somewhat open-ended. Why did you choose to conclude without resolution for the dictator's wife?

I did not want to give in to the temptation of an easy resolution because I do not particularly believe in one. Although an open ending might be more unsettling, it also feels more honest because this struggle is ongoing.

Democracy is on the decline globally. For nearly 40% of the world's population, including countries of the West, the questions asked in Secrets of a Dictator's Wife are a painful daily reality and since publishing this collection, the numbers have become even more alarming.

7. What has the reception been like so far from readers? What kinds of reactions and interpretations have you seen?

I always get amazed by how much people are able to discover in a single poem; sometimes more than I was aware of when I was writing it! I remember a piece that two people had strong feelings about, one saying that it took him to a very dark place while the other thanked me for helping her to find a source of light in the struggle she was going through.

To me, it is beautiful that poetry allows so many entry ways and I am very grateful when that happens with my poems as I want my writing to feel alive. It certainly was that way with this book – I loved the various interpretations I received, from taking it at face value to suggesting that it is a metaphor for migrants’ struggle to belong or a criticism of U.S. politics. Someone called it “shape-shifting” and I could not have asked for a better description.

I guess it is easy to forget how much in isolation writers work so every comment, and every review is golden and reminds us what we are doing it for – to spark a conversation.

8. You run creative writing retreats in Spain. In what ways does travel inspire your poetry? How do different landscapes come through in your writing?

I have been on the road for half of my life and it helped me to understand the Dictator’s Wife’s sense of being an inbetweener.

Nomadism and its effect on one’s identity is one of my major inspirations. Working in conversation with a local landscape is increasingly important to me. In this book, it was not immediately obvious because I decided that I did not want to place the story in a particular culture, simply because it would be easier to dismiss the dilemmas of the Dictator’s Wife as something that “could have never happened here.” Perhaps the last couple of years have shown us it does not take much to flip that script. So, the sea she observes is not as clearly defined as in poems I have written recently in the West of Ireland that strive to have in them the edginess of the cliffs – it is a very different coast to the soft lines of an Andalusian beach.

Sometimes, it can be difficult to navigate because I have to fight with myself to avoid centring every single poem around my love for the rawness of the Atlantic.

9. What's next for you? Do you plan to revisit this character or these themes in future writing projects?

The power struggle is definitely something I would see myself writing about again as it just feels both: timeless and yet very urgent. However, it might not be through the eyes of the dictator’s wife this time around – there are so many points of view that could inform this exploration!

At the moment, I am in the Westcountry School of Myth and this experience transformed the way I see the gift of poetry so I am excited to discover how this will translate to my next book. I am also lucky enough to be under Geraldine Mitchell’s mentorship through the Irish Writers Centre. I am working on a collection that initially was meant to be ecopoetry about climate emergency but recently, I discovered that it is about something else entirely. It touches upon themes of grief, reinvention of the language, and what it means to be of a place. It is also the most personal writing I have ever done.

Thanks for reading Scribblers, chat to you next Friday!

Take care,

Isabelle x