The Ache of Living: Launch day for 'The Soul We Share' by Ricky Ray!

Plus open submissions close in TWO DAYS!

A very happy Friday Scribblers,

It is just two days until we close our annual submissions. A big thank you for anyone who chooses to trust us with their words this year.

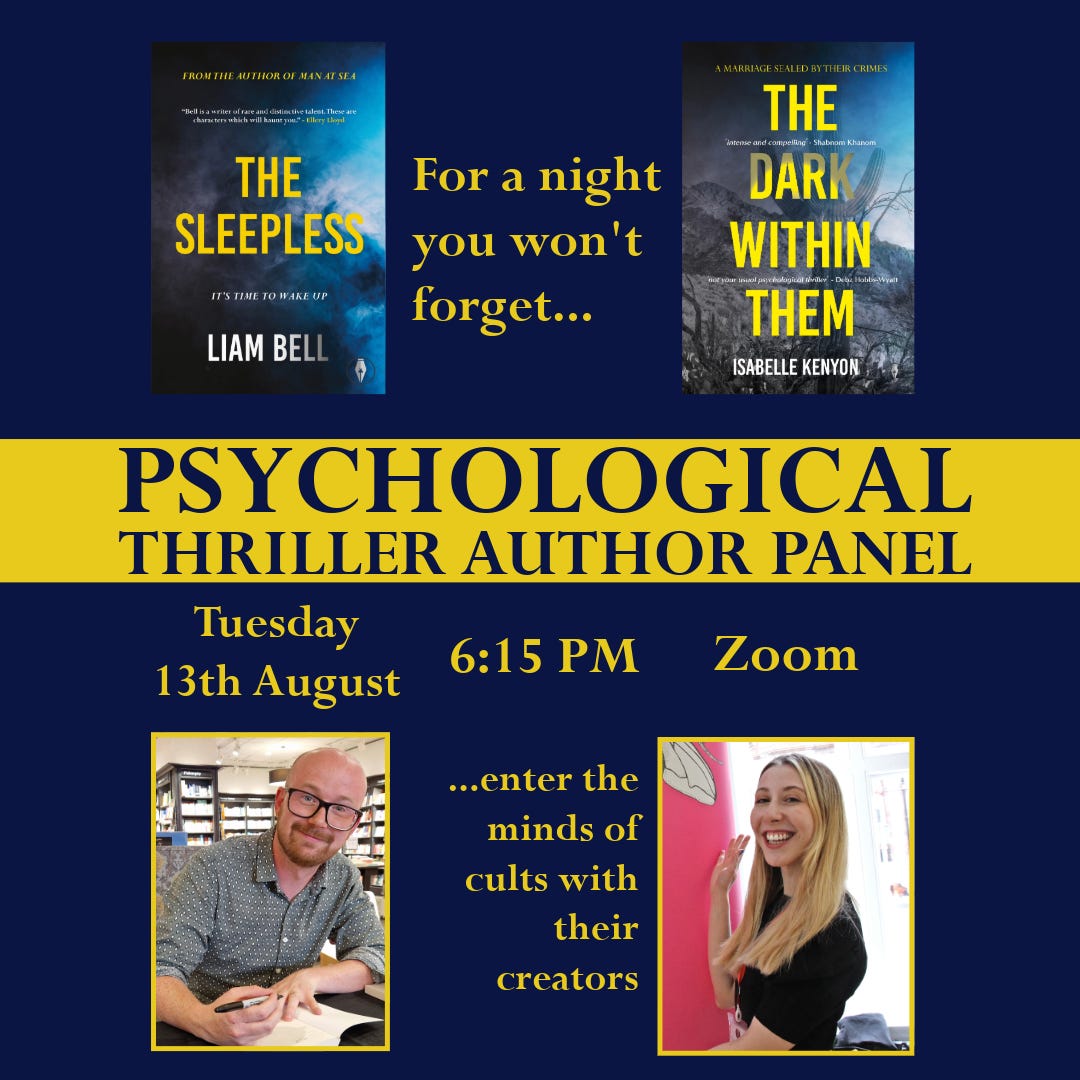

We’ve just launched a thrilling online event - for those of you who are fascinated by group-think, cult leaders and psychological thrillers, you’ll want to come along on Tuesday 13th of August. Tickets here. Louisa Wagstaff will be chatting to Liam Bell, author of The Sleepless, and myself, author of The Dark Within Them, to get to the bottom of just why we’re so fascinated as a society in psychopaths…

And today is a big celebratory day because it is the LAUNCH day for The Soul We Share by Ricky Ray!

The winner of the 2023 Aryamati Poetry Prize, THE SOUL WE SHARE treks through the scenic woodlands of New England, the concrete jungle of Manhattan, and the swamps of the Deep South, as lines between humans, animals and nature begin to blur and move in concert.

Ricky Ray measures the ache of living in a disabled body against the joy of 'being lived' by the places he inhabits. We accompany Ricky and Addie, his soul dog, on a journey through nature.

We had the pleasure of speaking to Ricky about his heartfelt new book, which can be found here.

Your collection is sectioned like a journey through song, could you tell me a little bit about your thought process behind this unique structure?

Hi! I’ll tell you a little story.

I think a book has multiple kinds of poems. Word poems, page after page. Feeling poems, which run through multiple pieces like a recurring heartbeat, or a shared soul, or the energy one body passes to another—a sense of something happening in the way the poems relate and interact: where they came from, how they sing, both individually and communally, how their voices form resonances that string the book together, and dissonances that strum the tension of those strings across the pages.

Then there’s the poetry of design, in the cover—which is the first poem a reader encounters—and in the font choices, the layout, the way the front matter greets a reader and the way the back matter wishes the reader farewell.

Another kind of poem in the book is the table of contents, or the line-by-line congregation of titles. One of my mentors taught that the table of contents can read like a poem, and is ripe for intentional refinement. I’d go a step further and say the contents page is always a poem, fully fledged, open to as much careful crafting as any of the verses, or open to letting the book’s arrangement create the contents poem on its own. Or a little of both.

I like that any of the titles can be an invitation towards a different starting point. I love that a book of poetry never has to be read front to back. It can be, is made to be, but there’s always the option to choose your own adventure, and the contents poem offers the many paths one might take.

Yet another poem in the book, akin to the feeling of soul that runs through the poems, is the book’s structure, which participates in the structure of existence itself, nature herself. Poetry, to me, is the way nature moves. Atomically, celestially, relationally, intimately. Moves with exquisite creativity and glorious patterns. When we look at the etymology of the word poetry, it roughly means to make, to create. Mother Earth is a maker, a poet, a poet of geophysical movements, a poet of species. Grandmother Universe is a poet, a poet of planets and stars, solar systems and galaxies, mysteries and infinities, all-pervasive. Their collaborative poetry literally shapes our lives, literally is the process of life itself, a process we’re fortunate enough to be part of, living poetry, and given the chance to contribute the artistry of our own lives and lines to their Earthly and Universal verses.

I’m telling you this because I think poetry is the music of movement. And I think symphonies are one version of humanity’s musical talents approaching a natural limit. A gesture of deeply devotional design made in honor of the patterns that allow us to sing. To hear. To feel. My beloved dog Addie taught me how to feel these poems, then to write them down.

So when I asked the soul that Addie and I and Mother Earth share what kind of structure the book might take, the answer came slowly, over years. I love symphonies, especially Mahler, and especially Mahler’s 7th. It’s a bit chaotic, rather intense, but full of so much feeling, it floors me every time. I wanted to honor that love for him and his work, and Earth and her works, and the poems Addie and I lived into being, so I sought to intuit a structure that aligns with all these interwoven rhythms.

To give the reader a sense of what we’re talking about, the book’s structure looks like this:

· Title Page

· Dedication Page

· Prelude

o Movement I

o Movement II

· Interlude

o Movement III

o Movement IV

o Movement V

· Coda

· Acknowledgments

· Notes

At first, I realized that the main parts of the book were not just sections, but movements, ways of being and living, with unique energies that build in progression. And I’ve always been fond of books of poetry that seem to have little preludes at the start, little orienting compasses—murmurs, intimations, a glimpse of the architecture about to be revealed. Poem 0.5, prepping us for poem 1. “The What of Us” felt like that prelude, its rhetoric setting the philosophical and emotional tones, the sections offering brief glimpses into the various kinds of weather in the book’s world, a world full of the selves we contain and the selves we belong to, my organism trying to turn feeling into song at the crossroads of that inner and outer selving.

The interlude came to me late, after the book was struggling for years and I couldn’t quite figure out what was missing. It’s essentially a small lyric essay. After 20 years as a poet, I began to write non-fiction, a cross between science, spirituality, memoir and eco-mysticism, something I call spiritual storytelling, another kind of poetry, a poetry of belonging, reminding us of the selves we belong to beyond our person, and the responsibility to extend our radius of care to the places we call home.

Movement III is a long, serial poem, kind of a counterpoint to the Interlude, which I now realize I might have titled Interlude II, but then the book wouldn’t have five movements, like Mahler’s 7th, so I think my original instinct was right. I rarely write poems of such length, and this was the only poem I wrote in a year, a poem that showed up and asked to be written all of a sudden on a single afternoon. I love those sudden thunderstorms of poetry, human consciousness buzzing like a beehive and barely able to keep up, and it’s probably a crucial ingredient of their magic that the storms so seldom occur.

To bring the composition to a close, like preludes, I love codas, the satisfying little extras that sometimes happen when the soul wants more. The encore. The last hug from a friend who’s moving away. The last, long look at a land one leaves, lingering until it almost hurts, but hurts in a good way, knowing you won’t return, but knowing the land will be alive in you wherever you go. The last days with a dying beloved, like Addie.

Addie, my soul dog and co-author, fought and bested brain cancer for over two years before she died. She had more living and loving to do. More to teach me about life. So she said fuck cancer and kept going. And when she lost some ability or other to cancer, she focused on the ones she still had. Then, about four months before the book was finished, she almost died. She had developed three more types of cancer. She had a 3+ hour seizure. But still, she wasn’t ready to go. She wanted to live to some limit only she kept in sight. And I was grateful. She astounded the doctors and gave us four more months to live in the love of goodbye. It was sweet. It was heartbreaking. It was so intimately poignant, every day, her body slowly failing and her spirit letting us do for her what she couldn’t do for herself. These months were the book’s real coda.

The coda in the pages, “The Last Walk,” was, for me, a spiritual necessity. It’s what I needed in order to cope at the moment of her death. It came to me—one of those rare storms—probably two years before she died. The only poem that has made me cry over and over again. I read it to her, in the minutes before her heart stopped, and I felt her magnificent spirit in every word.

Do you have any first memories of poetry, or an indication of what brought you to exploring this form of writing?

Memory is mostly shadow and mystery for me. I have aphantasia, the inability to visualize, which occurs along a spectrum, and I’m closer to the end of the spectrum where I can feel things but not see them. Dimly at best.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Publisher with a Conscience: Fly on the Wall Press to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.