Happy Friday Scribblers,

Allow me to introduce you to our latest signing: the third book by feminist fantasy author Rachel Grosvenor: Witchborne! If you adored the 100-year-old professor Wendowleen and her underground rebellion in ‘The Finery’ last year, you’ll want to check out our full 2025 book subscription and get yourself some goodies.

In the medieval town of Locklear, where women are continually under the threat of being accused of witchcraft, Agnes harbours a dangerous secret - she can touch fire without being burned. Torn between her innate power and the threat this represents. Agnes navigates a world where conformity is enforced by the ever-present hangman’s noose.

As she strains to uphold her own and her family’s reputation, a deal is struck with a suspected witch. But when this deal goes awry, her carefully constructed facade of socially-sanctioned womanhood begins to unravel as whispers of witchcraft grow louder. In a community rooted in the suspicion of woman and suppression of their power, can Agnes harness her strength to forge her own destiny, or will she succumb to the silence of countless women before her?

Whilst Grosvenor’s evocative pros transports us to the medieval past, Witchborne is a timely exploration of societies threatened by female power, the complexity of motherhood, and how the pressure to conform to societal expectations reverberates through generations.

Over the next two months, we have our busiest timetable of events yet - and we will be travelling all over the North and the Midlands, so we hope you can join us!

Book tours:

Lectures and marketing events:

Direct FOTW booking links are here, or at respective venue websites as above!

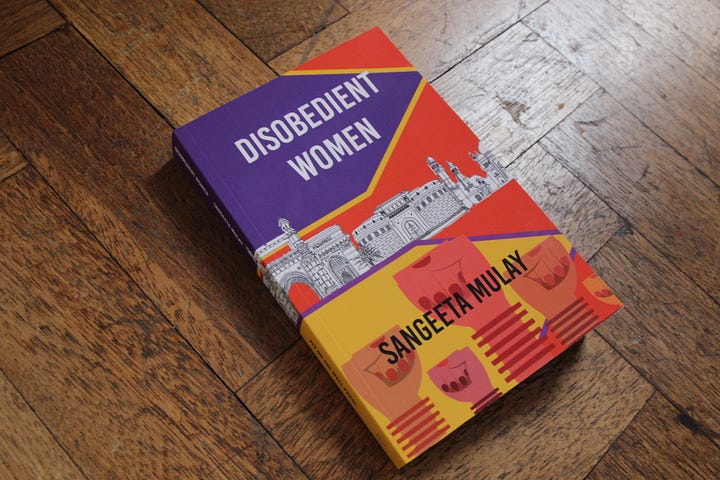

This week, we're featuring a thought-provoking essay by Sangeeta Mulay, author of novel ‘Disobedient Women, that explores the complex world of controversial literature. Through personal anecdotes and reflections on various controversial books, Mulay examines how her views on challenging literature have evolved over time. She presents a nuanced perspective on balancing free expression with social responsibility, introducing a framework for engaging with controversial works.

Let us know in the comments: what is your own stance on provocative literature? How do you navigate the fine line between supporting free speech and recognizing the impact of words?

(Code DISOBEDIENT20 will get you 20% off Disobedient Women until Monday!)

On books that cause offence

On a warm but cloudy day in April, I was sitting with my libertarian friend in an old café, discussing books, while our coffees lay forgotten on the side.

‘You claim to be a strong advocate for freedom of speech,’ my friend said, ‘a fan of Salman Rushdie and yet you vociferously deride the Charlie Hebdo cartoons. How do you explain this dissonance?’

I took a breath as I prepared to argue my case but realised that I did not know the answer. I needed time to gather my thoughts, to understand exactly where I stood on the freedom of speech vs controversy scale.

“I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound or stab us,” Franz Kafka once said. “If the book we’re reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow to the head, what are we reading for?” Now, I must admit, I’ve got a special place on my bookshelf for books that evoke a strong reaction; books that wound and stab; radical books; audacious books that rebel against conventional norms; books that stretch the boundaries and introduce ideas I’ve never considered before – yes, even books that cause offence - I love controversial books, but in the process of collecting my thoughts in response to my friend’s question, I gradually realised that while I do love controversial books, I love them with an attached caveat.

Let me explain.

(Some books referenced below contain spoilers!)

I grew up in a society where children are taught to be obedient and to colour within the lines; discipline is rewarded, and disobedience is punished. Against this background, imagine my awe and delight when I first came across an audacious children’s book called ‘Rule Is To Break: A Child's Guide to Anarchy’ by John Seven. Promptly, I purchased copies for children of friends and family, hoping the parents wouldn’t shun me for influencing their progeny in unsuitable ways. As I see it, it’s important to break convention in small ways now and then, and kids need to know this sooner rather than later. Not to say, break all laws and shatter all ethics, but understand that options and possibilities to rebel in small ways do exist. This book could have easily caused offence to parents who believe only in obedience and discipline at all costs, and this is a possibility that did not escape me. Yet I would file this book neatly under the ‘merely audacious’ category. Does this mean that only the books that do not cause offence to me personally get the green light from me? I realised I’d have to delve deeper in order to answer this question.

I grew up reading Enid Blyton books. These were the only books available to me as a child in India, and truth be told, I arrived in this country, expecting to see the England of Enid’s Blyton’s books. But as my ideas evolved, I understood the problematic nature of her books. Women, black people and LGBTQ communities have suffered decades of oppression, and when these groups speak, the others must listen. These groups have won rights after decades of struggle, and it will be doing a great disservice to these movements, if the problematic nature of a favourite author’s books is not called out. So while I don’t necessarily support deleting adjectives such as “fat” from Roald Dahl books, I do understand the problematic nature of Blyton’s books in depicting black people in an extremely offensive manner.

I admired the brilliance of Arundhati Roy’s ‘God of Small Things’, in which twins make love in what is described as an act of “hideous grief”, shattering notions of propriety by depicting what is normally considered obscene, as beautiful. I did not view the act as an act of incest but was convinced by their grief, and I cried with them. On the other hand, I found Vladimir Nabokav’s ‘Lolita’ inappropriate, and I cannot condone the sexually explicit descriptions of the relationship between a man and a twelve-year-old girl. Both acts are illegal under UK law, and yet, I was troubled by the depiction of only one act, and not the other, because the former is a relationship between equals while the latter is the rape of a child.

The fictional book, ‘The Help’ by Kathyryn Stockett became controversial because it was written by a white woman about the black experience, perpetuating stereotypes and playing into the white saviour narrative. While I believe the author is fully within her rights to write what she wants, she has to be equally receptive to receiving feedback on why her work is problematic. Everyone has, or should have, the right to write any kind of fiction, but as authors, it’s important to treat feedback with humility and be open to criticism. It’s also important to understand white privilege, or as I call it, the majority privilege, where if you do use your power to usurp the voice of the historically supressed minority to make your point, then it’s crucial to understand the reason why that’s problematic.

The next time I met my friend in the same café, I had my answer ready. ‘I know why Salman Rushdie has my approval, but Charlie Hebdo does not,’ I said as soon as we settled down.

‘Ah! The freedom of speech vs controversy debate,’ my friend said as she sipped her latte. ‘Go on then, the stage is all yours.’

I took a breath and then proceeded to deliver my little speech. ‘Simply put, I approve of books which punch up rather than down,’ I said. ‘Books that make the privileged majority squirm; books that offend regimes and the power holders; books that offend power, will always have a special place on my bookshelf. Books that punch down - books targeting the voiceless minorities or books offending groups which have been historically oppressed, make me uncomfortable. I view Salman’s Rushdie’s fight as one against a powerful regime whereas Charlie Hebdo cartoons were published in a Western country targeting a religion of their minorities. I stand for their right to publish what they want, but just because I stand for freedom of speech does not mean that I have to like their cartoons. I don’t believe in book bans, but I do believe in book bins. If a book makes me squirm, I simply bin it (metaphorically speaking). Bin, not ban, is the mantra I go by.’ I cleared my throat, but I wasn’t done yet. ‘If a book causes offence to a historically suppressed group which has spent decades in earning their rights, then I consider the book problematic. If a book causes offence to the minority population of a country, then I consider the book problematic. Everything else is okay.’ I took a sip of my tepid coffee. ‘So, there you have it. It’s all about who you’re punching,’ I said with relief, glad to have explained my stand to her, and most importantly, also to myself.

Thanks so much to Sangeeta for this thought-provoking piece, we’re excited to hear your thoughts in the comments!

Talk soon,

Isabelle