July news: new hires, celebrations of reading and the 'doppelganger of Death'

Pete Hartley chats crafting ghouls and uncanny sensations

A very happy Friday Scribblers,

I had the wholesome joy of visiting Priestnall School this week, for a celebration of reading event. I talked about my favourite books growing up, donated books to their new school library and awarded avid readers with awards!

This week has also been a busy one because we welcome two part-time team members for the first time to the team - Louisa Wagstaff and Avrilella Hussain - assisting with our PR and Events strategy.

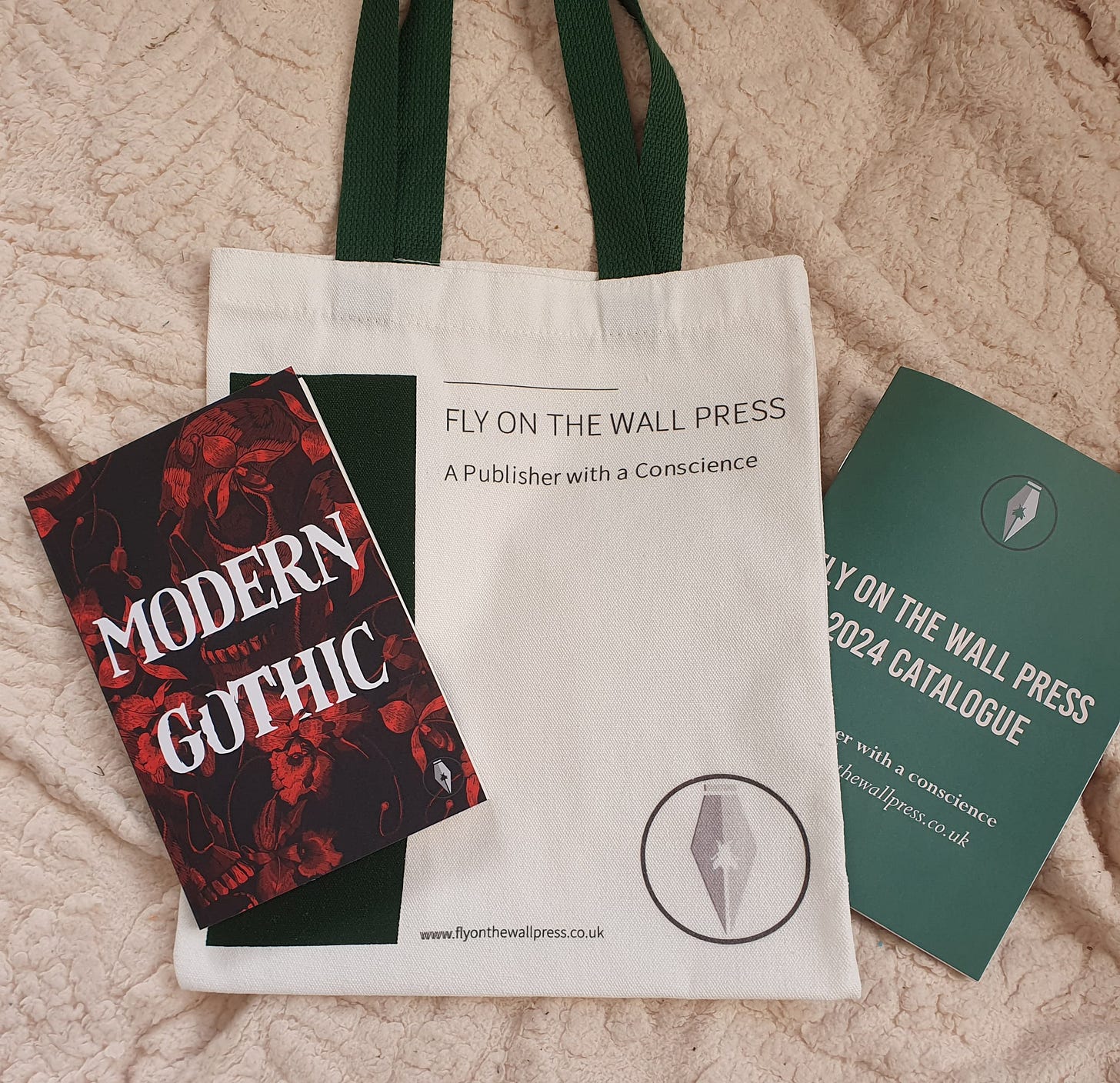

Just announced - we’re going on tour with anthology ‘Modern Gothic’!

The Manchester 11th date is now open for ticketing here

…As is the Liverpool 23rd date here

…And i’ll keep you updated when the others are live!

Plus our Bookseller article is out…

The article explores the pricing issues in the publishing industry, particularly their disproportionate impact on small, independent publishers.

I deal with the gap between UK and US book pricing and ask searing questions about what the situation in the UK demonstrates about the value we place on literature, education, and the representation of diverse voices.

Check out the full article here. (If you can’t view it for free let me know as I may schedule it via Substack for you in full!)

Today we speak to Modern Gothic short story author and playwright Pete Hartley about his Edwardian magician tale: ‘Livid’.

‘Livid’ by Pete Hartley - his ‘Modern Gothic’ story in brief!

An unnamed narrator hears a woman repeating phrases to him that were said to him in a dream and awakens frightened, struggling to understand the significance of these phrases. Seven months later, at a theatre performance, a spotlight shines on a woman looking just like his dream. She also repeats the key phrases from his dream. Deeply disturbed, he travels to the only person he knows who could help explain the mystery - a Mrs. Moritz, formerly the glamorous magic show assistant Lazuli.

Hartley’s story will attract readers who enjoyed Laura Purcell’s Victorian gothic thriller The Whispering Muse, which also uses the setting of theatre and the stage as a backdrop for her tale. Another is Robert Louis Stephenson’s Jekyll and Hyde, which also explores psychological elements and features an unreliable narrator.

‘Livid’ opens with the feeling of being trapped in a dream, an uncanny sensation which I’m sure most of us have experienced. This very feeling is very Freudian in that what is repressed comes to light in our subconscious minds. How does this ‘return of the repressed’ link to the gothic themes of your story?

Gosh - straight in at the deep end! My chief impression of the Gothic mood is one of the past claiming dominion over the present; and the future. It is a memento mori that will not allow us to forget what we have inherited and what we will become. This frequently happens in dreams. Sometimes relatively insignificant events from our past are amplified into monstrous melodramas. ‘Livid’ inverts this. It is not a dream recalling a real-life event but a real-life event reviving a dream, or so it seems. That’s what captured my interest, and I hope will do the same for the reader.

At times, the narrator of ‘Livid’ cannot distinguish between dreams and reality. I understand this was what happened to some volunteers who took part in a research project on sleep deprivation. They started dreaming while they were awake and could not always detect which aspects of their perception were real. The validity of perception becomes a major theme of ‘Livid’ as the story unfurls.

As for the repression, well, it turns out that there are several aspects of the protagonist’s relationship with the subject of the dream that he may well have been trying to keep a lid on. He experiences a weird cocktail of emotions due to the unintended consequences of something he wrote. That mix includes an unlikely pairing of satisfaction and guilt. He has kept certain things to himself which means, of course, that he has to live with them.

Gothic fiction often manifests as a testament of an aggravation in which the undesired, or desired, refuses to be buried. That certainly happens in ‘Livid’.

Alban, the narrator, often questions the figure of ‘the double’ or ‘the twin’, and this is a big theme of the story. Of course, the doppelganger is a gothic trope in itself- was this something you wanted to explore in ‘Livid’?

The story starts with an audible double. Alban, recognises something he hears as both a perfect and imperfect replica of something he has heard before. The image he sees is similarly deceptive; it looks both familiar and unfamiliar. The impact on him is compounded by the fact he is sitting in a theatre where the blatantly false is used to reveal hidden truths, and because the theatre management are bewildered by what he said he witnessed. He seeks help by going to visit the one person who can clarify matters: the person he thinks he saw on stage. He is both reassured and further troubled by this confidant and from that point on he is never sure if he is seeing what he thinks he sees.

I see Gothic as the doppelganger of Death, the angel who starts waiting in the wings from the moment we enter the womb. It is the constant companion who simultaneously walks alongside, plots behind our back, and lies in wait ahead. It often wears a disguise as something life-enhancing and attractive. This is a frequent image in Gothic fiction and can be considered as an incarnation of hypocrisy, which is a particularly cruel duality, and high on my list of things to hate.

I didn’t deliberately set out to include the doppelganger in ‘Livid’ but in a strange way it was unavoidable, as the story itself is one, or at least the opening paragraph is. I used that speech as the start of a play I wrote and staged in 1996. The first page of the story recreates what I actually saw on a stage. After that the story goes off in a completely different direction, and that alternative appearance was what I wanted to explore.

Incidentally, I have always been a great exponent of the ideas of the French actor and director Antonin Artaud (1896 – 1948) whose most famous book was entitled ‘The Theatre and its Double’. He said that theatre was the double of life, but that theatre is life lived with authenticity, without lies and without pretence, which seems entirely incorrect, but is actually utterly true.

What is your take on spirits? Do you believe in ghosts and spectral hauntings?

The theatre director Peter Brook said something very interesting about ghosts when he was discussing the motivations of Hamlet. He said that you don’t need to believe in ghosts to see one. If you see a ghost, then at that moment, you believe in it. This is irrespective of whether or not the ghost is actually there.

Of course, he is absolutely right. If you see a ghost, it doesn’t matter whether the ghost is in your bedroom or just in your head. The physical, psychological and emotional consequences will be the same. I think this is a really important observation. We govern so much of our lives by what we visualise.

The first pieces of prose that I had published, way back in the early 1980s, were Christmas ghost stories. They appeared over a number of years in magazines and on regional radio. When I later assembled them into a collection, I included a commentary stating that I did not believe in ghosts, but was frequently haunted. That remains true.

Setting the novel in Edwardian England allows you to tap into that era's societal constraints and fascination with the uncanny. What sort of research did you do to authentically capture that time period as the backdrop?

I am the fifth child of a father who married relatively late for his generation and hence was old enough to be my grandfather. He turned eleven at the end of the year in which ‘Livid’ is set and my mother was born two years later, in 1915, so my sisters and I have a reasonable amount of memorabilia from that era. Once the story began to emerge, I delved into dusty boxes and revisited sepia prints. Nearly all the photographs are of wedding groups, or formal occasions, but despite their limitations they helped considerably with costume detail, period atmosphere and social attitudes. My father left a memoir chronicling his youth, which I transcribed a couple of years ago, and that was very much in my mind.

I’ve always been interested in the history of my home city of Preston, which like Manchester, Liverpool and many other northern conurbations, mushroomed during the Victorian and Edwardian periods. I already had a pretty solid knowledge base and some often-thumbed local reference books. Appropriately, it was theatrical history that proved to be pivotal in making the setting Edwardian rather than Victorian. It all comes down to the spotlight which illuminates the opening image. I had to ensure that type of a lantern was a feasible component of a theatre at that time. Nerdy, but crucial.

The character of Lazuli is extremely fascinating. Her relationships with those around her are central to the story yet she remains a complete mystery- how did you go about characterising her? Was she inspired by a real-life figure, or anyone you know?

I share your appraisal of Lazuli. She both delighted and disturbed me. I have no idea where she came from, and that is a source of some ongoing introspection. I do have a strong visualisation of her but cannot think of anyone I have known like that, though I’m sure we’ve all sometimes suspected that we were being presented with a veil of benevolence disguising something less sympathetic.

With the benefit of hindsight, I can speculate about some aspects of her behaviour, but she remains strongly enigmatic. It could be that she was so steeped in the smoke and mirrors of the theatre that the machinations of that medium became her offstage modus operandi. There does appear to be a sleight of hand at work in her management of those around her. The discretion and dexterity needed for her previous occupation are transferable skills that she redirects astutely. On the other hand, I am not at all sure how responsible she is for what happens in the story and the consequences for Alban. I am as perplexed as he is, and I really like that. Readers can form their own opinions.

I consider it over between Lazuli and me, but I’m not confident that she sees it that way. I’ve got a feeling she’ll give me a call. Probably in a dream.

Another key theme is the role of theatre in Edwardian society. Has theatre always been a passion of yours? What made you decide to construct a story around it?

About the same time as my Christmas ghost stories were finding a market, I was fortunate enough to have some luck with playwriting. The BBC recorded and broadcast a thirty-minute radio play and some stage plays received amateur and professional productions. A partial consequence of that was an invitation to run a series of drama workshops in the evenings. Over a period of some seven years those classes evolved into a full-time teaching contract and a career lasting until 2017, when I retired. I have, therefore, been backstage in a great many theatres, including some built over a hundred years ago and containing the original features such as complex rigging for ‘flying’ scenery in and out, and sloping floors with trap doors. I expected those attributes to feature significantly in ‘Livid’, but the story didn’t demand them as much as I had anticipated. Theatrical trade secrets and performance techniques played their part, however, and theatre as an art form insisted on being centre stage. As mentioned above, perception is a major theme of the story, and in theatre, perception is all.

Down the years, in addition to teaching drama, I also ran a string of small, profit-sharing, fringe theatre groups in order to try out a few things with my teaching associates and give more opportunities to former students. For those youngsters who aspired to be professionals, it was often the first time they were paid for working at their passion.

In 2010 we took a show about the teenage William Shakespeare to a Tudor stately home. The events manager told us she had previously worked as a magician’s assistant. She did not break the Magic Circle confidentiality code, but said enough to make me realise that the ‘assistant’ was not only the hidden power behind the magician’s throne, but also the battery pack concealed within it. Without her he was virtually powerless. This became the plot engine of ‘Livid’ and the reason I thought the story might sit well on the Fly on the Wall platform.

Thank you so much for taking the time to chat to us Pete! Pre-orders for Modern Gothic can be found here.

Until next week,

Isabelle x

Modern Gothic sounds great! I love the uncanny… M R James, Susan Hill etc ..

Very interesting interview with Pete Hartley. I hope you’re visiting London or the Lake District for a launch… The New Bookshop in Cockermouth is always up for writers talking about their books!

Otherwise I can make the online launch.

Looking forward to reading Modern Gothic