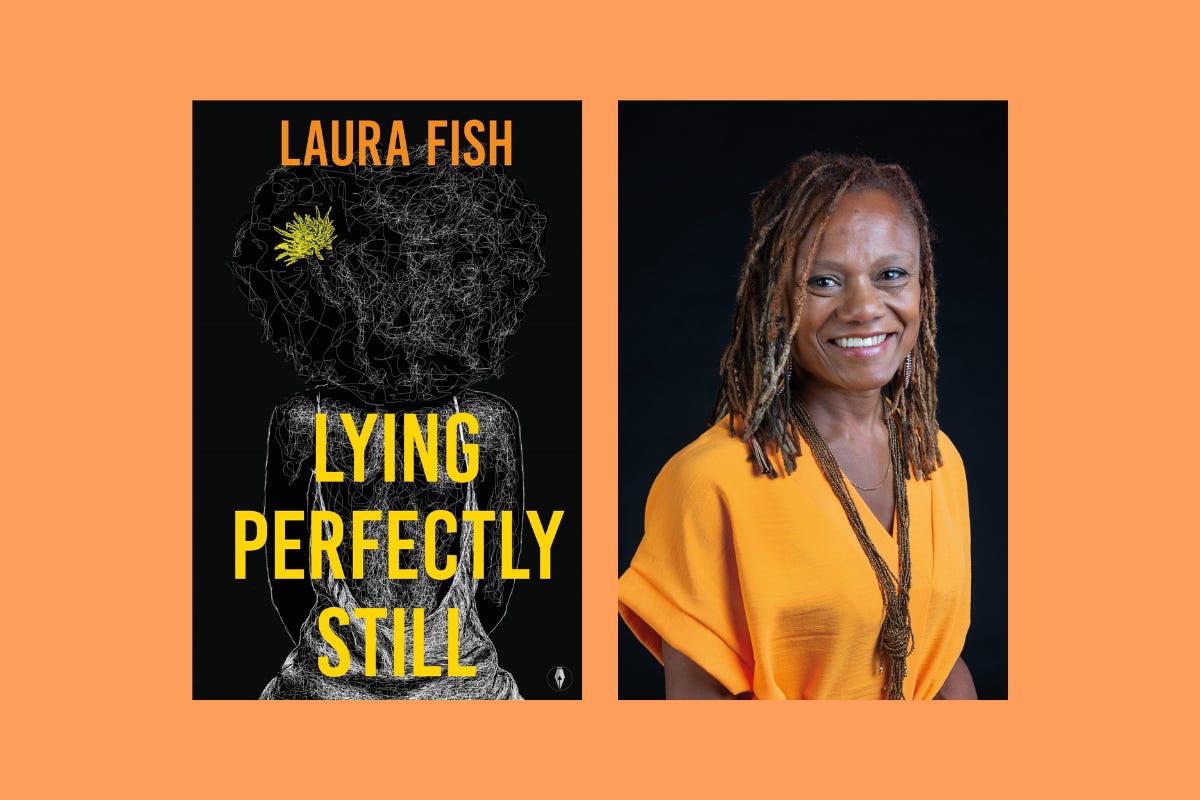

'If someone could tell your story, what story would you like to be told?' Flying the flag for Lying Perfectly Still by Laura Fish

Lying Perfectly Still, the latest novel from Women’s Prize longlisted author of Strange Music Laura Fish, is a searing inside perspective of the clashes between wealth and poverty in Southern Africa.

Hello there Scribblers,

It’s a strange week launching the last work of the late Laura Fish - but I couldn’t be prouder of ‘Lying Perfectly Still’. It’s the epitome of the generosity of Laura’s spirit. Whilst living and working as an Aid worker and reporter in Eswatini, Laura recorded interviews with several women who were HIV positive. She asked them, if someone could tell your story, what story would you like to be told? And she went from there. So the characters that Koliwe interacts and connects with via her work for British Aid, such as orphaned Thandi, who goes missing, are based on real people. You can read an interview between Laura and New Writing North in full below, and join us tomorrow lunchtime at Newcastle Central Library.

Great to see Guildford Book Festival championing the short story with our 2021 shorts season writer Ruth Brandt and our 2023 best-selling author, Alice Fowler (join Alice for an online ‘How-To’ on Book PR and Marketing online next month here).

And Rennie Parker (Everybody’s Reviewing Journal, University of Leicester) praised the authenticity of working-class Wakefield (couldn’t resist the alliteration!) in SJ Bradley’s short story collection; 'And that’s the thing about this collection; no matter how clueless or downtrodden her citizens may be, there is always someone, somewhere or something which makes the struggle worthwhile. These characters are not being written about from the outside: they are sat along with, interacted with, and lived through... ' Grab a copy here

And if you’re in Manchester, you can join us next Tuesday on your lunch break for a fun deep dive into all things gothic, with playwright and short story writer Pete Hartley! (House of Books and Friends, King Street)

A heads up that our mini window starts on the 1st of November - if you’ve a poetry collection or a short story collection that’s burning a hole in your notebook/desk/pocket AND you’ve NOT submitted to us yet this year, guidelines are here. Summer 2025 open to all genres as usual.

Today I’m passing over to New Writing North’s Hana Sandu and our wonderful novelist Laura Fish, for a thought-provoking deep dive into award-winning novella ‘Lying Perfectly Still’ , released just yesterday!

Lying Perfectly Still: Interview with Laura Fish

Posted 19 September 2024 by Hana Sandhu and Laura Fish

Lying Perfectly Still, the latest novel from Women’s Prize longlisted author of Strange Music Laura Fish, is a searing inside perspective of the clashes between wealth and poverty in Southern Africa. Get a glimpse into some of its themes – doubling of identities, elemental symbolism, attitudes to aid work, and more – in our interview with Laura.

Hana Sandhu: Lying Perfectly Still tells the story of Koliwe as she travels from Oxfordshire to Swaziland as part of a Western aid mission during the HIV/AIDs crisis in Southern Africa. What drew you to this historical moment?

Laura Fish: The book is written in response to my experience of working in Southern Africa as a researcher and a stringer – a freelance journalist, contributing to news reports and features for broadcast on BBC World Service Network Africa during the HIV/AIDS crisis in the late 1980s. I lived in Mozambique, Angola and South Africa. When I moved to Eswatini (formerly Swaziland) the country’s HIV infection rate was over 42% among women of child-bearing age, which was estimated to be the highest HIV rate in the world, and the numbers testing positive were continuing to rise. I have since been haunted by the extremes in poverty and wealth and the gulf of understanding between the white expat aid workers and the local people they were there to help.

HS: As soon as Koliwe arrives in Swaziland, she is aggressively pursued by her misogynistic and abusive boss, Cameron. You powerfully depict Koliwe’s particular isolation as she is favoured above the local population by the British expats, but equally vulnerable to the predations and misogynoir of her white superior. How do these intersections of identity shape Koliwe’s journey?

LF: Lying Perfectly Still is set at a time when the term ‘intersectionality’ was not commonly used. However, the intersections of Koliwe’s age, skin colour and gender contribute to the power imbalance in her relationship with Cameron, her white, middle-aged boss, and connect with the three issues at the heart of the book: the value placed upon black lives; the exploitation of young women; and a global pandemic – HIV/AIDS. Koliwe’s fear of having contracted HIV takes her deep into the mountains and through the looking glass into something approaching the experience of local women, enabling her to finally make common cause with them. One of my aims was for all these elements to combine to shape Koliwe’s journey, forge her new identity and provide a counterpoint to otherwise radically different lives.

HS: Lying Perfectly Still serves as a searing critique of the imperial attitudes and policies shaping UK foreign aid. Do you see any change within the aid sector in addressing these entrenched power structures and attitudes?

LF: During the mid-1980s when I worked for Save the Children in Sudan, there was a surge in celebrity engagement in the Global South. The general attitude seemed to be that what Western aid workers lacked in cultural awareness and sensitivity could be made up for by good intentions based on inherent Western moral standards. I believe there has been immense change in UK aid and development since then. Although paternalistic attitudes still exist, my understanding is that local people are now more likely to be employed and listened to by development agencies and there is far more caution around cultural appropriation and accountability, and awareness of colonial legacies of disenfranchisement. The UK government’s current aid strategy prioritises sustainability, reliable investment, empowering women and girls, climate change, biodiversity, as well as life-saving humanitarian assistance to those in greatest need.

HS: I was struck by the novel’s elemental lifeforce, the symbolism of fire and water in its pivotal moments. Was this a conscious stylistic choice from the beginning, and how does this relate to deeper issues of ancestral knowledge, death rites and colonial trauma?

LF: Eswatini is one of Africa’s smallest countries, and yet Sibebe Rock is the world’s largest granite pluton (a deep-seated intrusion of ingenuous rock). The country has the highest recorded number of lightning-related fatalities (totalling 123 between 2000-2007) and one of the last remaining absolute monarchies. I wanted to capture the feeling of being immersed in wild and beautiful scenery, and the incredible force of storms, for when lightning strikes the granite mountains small fires often flare up.

I also wanted to offer a sense of Eswatini’s rich vibrant culture, because the Reed Dance and Incwala are spectacular annual cultural celebrations, and they show that despite the constantly changing nature of life, beliefs in ancestral knowledge and culture can run as the seams of gold within the rocks.

I have nearly always lived close to rivers and I am interested in the idea that one can never step into the same river twice. At an earlier stage, the working title was The River, and the river has remained a motif running through the book. The symbolism of fire and water were therefore stylistic choices.

Koliwe changes constantly like a river, and the Eswatini her father knew is not the country she experiences. She encounters the trauma and scars of colonialism and the devastation of a pandemic.

HS: There’s a lot of doubling in the novel – for example, the main character shifting between Koliwe and Xolile, and the figure of Thandi/Gift. What is the significance of this doubling?

LF: Koliwe and her father are in a minority as the only black faces in an English rural setting. Strands woven through the narrative include mirrors and doubling, disparities in cultural understanding – and in poverty and wealth – between local people and international development workers, the exploration of identity, alienation and connection, privilege, grief, entitlement and abuse. Koliwe lives between contrasting cultures. She feels as though she is two people in one body. There is the English Koliwe, and the African Xoliwe she is just beginning to come to understand. The significance of the doubling is to explore some of the nuances, complexities and the limiting nature of attaching certain labels, such as nationality and cultural identity, and to address how a person might simultaneously carry opposing feelings of dislocation and belonging.

Thinking of Laura now and always, you can pick up a copy from us direct here or in your local library or bookshop - and if it’s not yet on their shelves, they’ll be delighted to order in for you.

Take care of yourselves,

Isabelle x