"I am fascinated by the way that feminism and motherhood clash, rather than intersect."

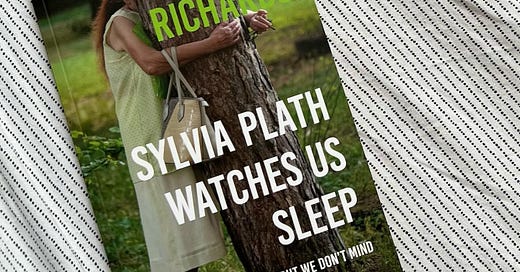

Victoria Richards on womanhood, the uncanny and ‘Sylvia Plath Watches Us Sleep’

As part of Joe Bedford’s interview series Writers on Research, he spoke to author Victoria Richards on the research process behind her collection Sylvia Plath Watches Us Sleep… But We Don’t Mind (Fly on the Wall Press, June 2023).

One of the core themes of Sylvia Plath Watches Us Sleep is, in my reading, the human capacity for compassion in the face of suffering. In some stories, characters are made to endure personal suffering, or witness the suffering of others; in others, it is the reader who is challenged to respond to that suffering. But in all, the difficulties of enacting compassion in the face of horror, sadness, etc feels ever-present. Is that a fair reading? How do you feel the difficulties of compassion function both within these stories, and within your personal relationship with the world?

I believe that compassion is the key to our humanity. Without it, we are little more than selfish, cold, avaricious consumers (of time, of material goods, of other people’s love and loyalty). It is through compassion and empathy that we are able to love and be loved; it is through human connection that we achieve something akin to God, or nirvana. Suffering and pain are made palatable by their opposites: love and compassion. Yet it remains our greatest challenge: can you feel compassion for someone who has wronged you? To be able to do so, you must be able to put yourself in their shoes and understand their motivation. If you can do that, you release yourself from pain and suffering. It is loving the one who has wounded you that ultimately sets you free.

Compassion as a quality is something that has captivated me since I was a young child, and I still don’t entirely know why. I remember my parents describing me as “too sensitive” because I would cry when the cat caught a bird and brought it into the house. I remember persuading my dad to let me put an advert on Teletext (showing my age, here!) to advertise for pen pals – in the ad, I described myself as “compassionate” and asked anyone reading to, “please write to me with all your problems”. I was only eight years old. I grew up with a natural ache for others – when I was ten, I told my teacher that I wanted to be a psychologist.

I don’t think we should hide from suffering: let it be witnessed; let it be understood. Let us place ourselves in the shoes of the wounded and the person doing the wounding; let us attempt to understand the duality of these two concepts intimately, close up. I suppose, deep down, I don’t believe in inherent ‘evil’. I don’t believe anyone is ‘all bad’. I believe everyone can be ‘saved’. But to be ‘saved’, to be ‘made good’, we have to be understood.

More simply, I enjoy writing an ‘unlikeable’ or ‘damaged’ character, because it forces the reader to question what it is they like or don’t like about them. Sometimes, what we don’t like in a character can tell us an awful lot about what we don’t like in ourselves.

I was taken by your use of the language of emergencies, particularly the way you voice formal emergency guidelines in ‘Never Run From Wild Dogs’ and ‘Drowning Doesn’t Feel Like Drowning’. Writing within a world in which the word ‘emergency’ feels like it is gaining increasing prevalence, what effect does the sometimes uncanny-sounding vocabulary of emergency advice have on you? And what inspired to work with it creatively?

The motivation for using the field research on drowning came from a news story I was working on in my day job as a journalist. We were writing about the number of drownings that happen on busy summer days in popular seaside beauty spots, but which go unnoticed, because – as the adage goes – drowning really doesn’t look like drowning (or, at least, it doesn’t look an awful lot like the drowning we see in movies, where people yell and wave and shout and make a lot of noise).

Drowning is a lot more subtle than we might think: and that made me think about the way we present ourselves to others in our daily lives, how we can be ‘drowning’ right under the noses of our colleagues, our friends, our loved ones. We don’t cry for help, very often. We don’t make a huge fuss and attract attention. We don’t ask to be saved. We just drown slowly and quietly, in plain sight. The human experience can be very lonely – and surrounded by ‘emergency’. The trouble is, it’s a silent emergency most of the time. The people who shout loudest are not always the ones who need the most urgent help.

On a more practical level, I enjoy the mix of ‘official’ and ‘lyrical’ language. The former can sometimes present itself as a ‘found poem’. Emergency guidelines can sound dull and mechanical – but look at what they’re describing! The loss of something valuable, the loss of vitality, the terrifying end to life… all dressed up in ‘four handy steps’. Guidelines like these take the thing we fear the most – death – and make it tangible. They make it real. They give us a crutch or a life buoy; numbered instructions for how to cope with something terrible and unimaginable. In a crisis, that’s something we all need, but rarely get. I like the juxtaposition of the emotional and the practical. One only makes the other feel more accentuated, stark and profound.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Fly on the Wall Press’s Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.