An MP at loggerheads with an idealist, a bet and a hungry polar bear

A Christmas-special extract, and an event look-ahead!

Well hello Scribblers,

This week I had the joy of headlining Manchester spoken word night Verbose with Rosie Garland! It was a magical evening of shooting stars and magical realism (Rosie, early preview of ‘Your Sons and Your Daughters are Beyond’) and Mormons awkwardly navigating an underage party (me, ‘The Dark Within Them’ sorry, Merry Christmas!)

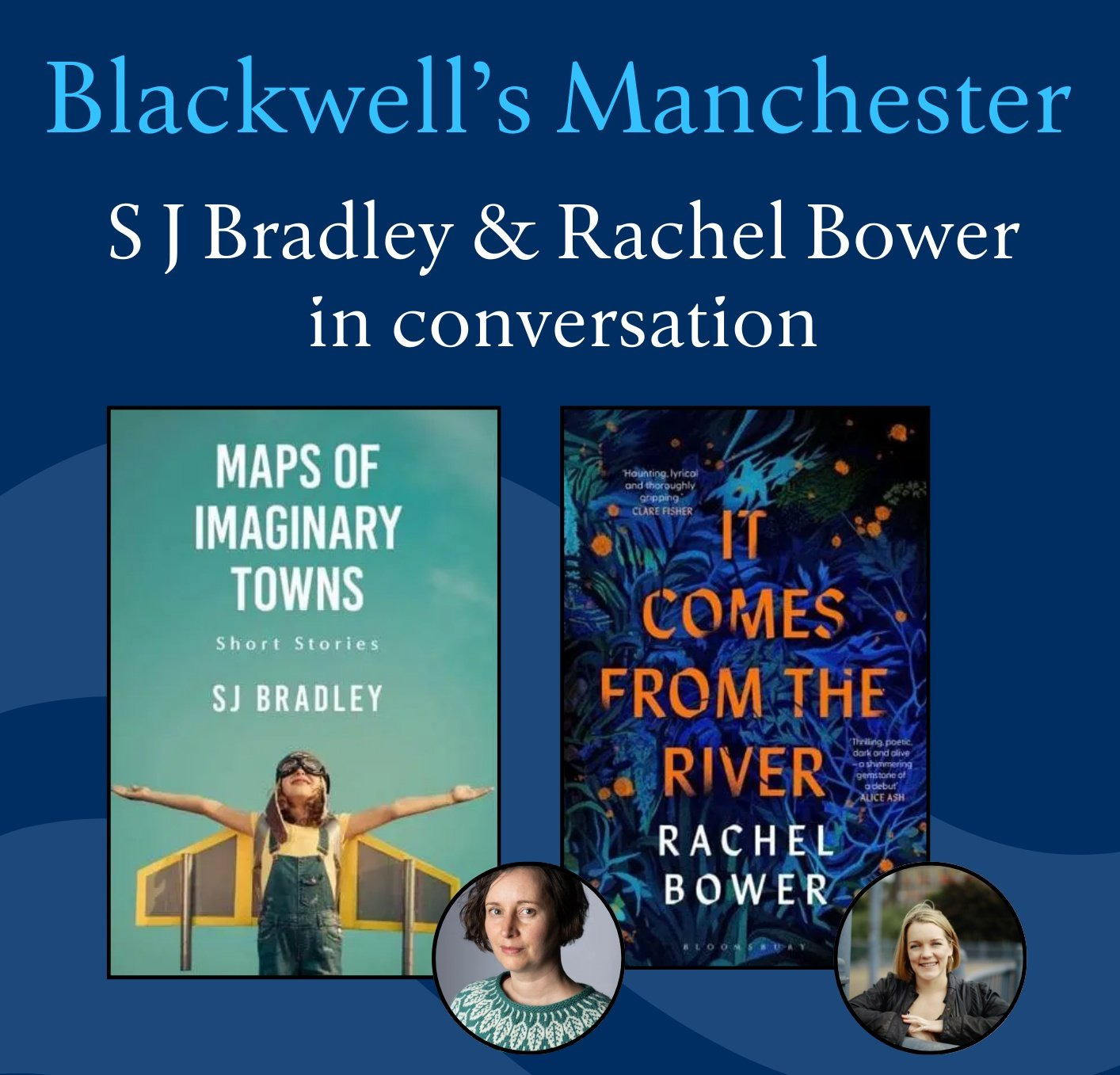

And we’re teaming up with Bloomsbury to celebrate our talented ecopoet Rachel Bower’s (‘These Mothers of Gods’) debut novel! On February 12th, SJ Bradley (‘Maps of Imaginary Towns’) and Rachel Bower will read tales of northern resilience at Blackwell’s Manchester. I’ll be hosting, so I’ll hopefully see you there!

Now imagine this...

Two men floating away from Greenland on an iceberg, with only a hungry polar bear for company; the outcome of a bet or wager, foolishly committed to decades before.

The two men, a blustering Tory MP - climate change denialist, Monty Causley - and an idealist climate scientist - Tom Horsmith - have made a drunken bet, which will change the course of their lives and of those around them. The deadly wager: in fifty years, either the sea will rise enough to drown Monty in his beach-front home, or Tom will accept jeopardy himself and walk into the sea and drown.

The story of The Wager and the Bear by John Ironmonger is entwined with the love story of Tom and Lykke Norgaard, a climate scientist and fierce advocate for the environment. John Ironmonger's latest novel, a companion to his international bestseller, The Whale At The End Of The World, also features a host of warmly drawn Cornish characters set in fictional St Piran. All are front-seat observers to an unfolding climate crisis.

Yet this is not a hopeless tale. Like its companion The Whale At The End Of The World, it might be described as 'heart-warming dystopia' (Elle UK). Ironmonger's key characters are engaging and believable; his plot well-paced, despite spanning five decades and his message compelling and timely.

So shall we delve inside the pages and read an extract? I think we should…

An extract from Chapter Two:

A great many legends are told of the village of St Piran; so many, it is difficult, sometimes, to sift the truths from the fables. There are those in the village (just as an example), who say the ancient stone boulders that mark the two ends of the harbour wall are the mortal remains of the fishermen, John Brewster and Matthew Treverran, who were turned to stone (and justly so) for playing dice on a Sunday. Others will tell you that the harbour walls themselves are nothing but the open arms of a knocker – a Cornish demon from the tin mines at Botallack – who drowned in the waters of Piran Bay while fleeing from St Michael after a violent dispute at cards. These are the kinds of stories you will hear if you spend time in this village, if you have an honest face, and if you have the patience to listen. There are some in the community who still, to this day, hide the body of a cockerel in the coffin of a loved one. The fowl will be revived in the next world, and his appearance will remind St Peter of his denial of Christ, for it was as the cock crowed that Peter committed his mortal sin. The memory of this, and the attendant shame, will tempt the saint to be merciful when he judges the deceased. So goes the logic. It is not unusual for villages in Cornwall to cling to traditions like these, but St Piran, you might well think, appears to have more customs than most. Every Christmas, the children of the village parade up the hill by candlelight beneath the giant effigy of a whale. This, they will tell you, is in memory of a man who saved the village from one of the great pandemics, when he rode onto the beach on the back of a whale.

They are idle tales, the tales told in St Piran. Some, like the tale of the fishermen turned to stone, are brief events. You might have been in St Piran on the day they happened, and still have missed them. One moment John and Matthew, the dice playing fishermen, were flesh and blood. The next instant they were boulders propping up the harbour walls. No one, so far as we know, was there to witness it. Other stories unfold over weeks. Or even months. And then there is the story of the wager and the bear. Once there was a time when everyone in the world knew this story. Or part of it. They will tell you it has something to do with a bear. And it does. But this is St Piran. This is where the story started, and also where it ended. They have their own way of talking about things here. So, for them, this story is perhaps the strangest tale of all. It unfolds not over days (as the newspapers might have suggested), nor weeks, nor months, but decades. It is a story of human lifetimes. Martha Fishburne told parts of the story to the children in Piran School, and in due course some of them wrote down the episodes they could remember. Charity Limber, who cleaned at Marazion House, heard a great deal of the story from Monty Causley, and she told it all to Jeremy Melon, and Jeremy wrote some of it down, but only part of it, for he didn’t live to see it all through. There are photographs if you care to look hard enough for them, and a great many accounts in old newspapers, and even one or two older residents who perhaps remember some of it. There was even a film made once, and a stage play, and most school history books of the period and online encyclopaedias have some version or other of the events. But none of these allowed the whole story to unfold. And this, perhaps, is why the tales are still told in St Piran. It hasn’t snowed in the village for fifty years, or maybe more, but there are villagers today who still display a snowflake in their windows in June, and this, they will tell you, is to remember the wager and the bear.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Publisher with a Conscience: Fly on the Wall Press to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.