'An Arsenal of Gothic Tropes': We Speak to Journalist Michael Bird about his story in upcoming anthology 'Modern Gothic'

Plus we went to the British Book Awards!

Happy Friday Scribblers,

I had an amazing time at the British Book Awards this week - what a glamorous event it was! Meeting Jacqueline Wilson was a childhood dream and highlight, and the whole event certainly inspired me, believing even more fervently in the power of words! I managed to pop into Foyles Charing Cross and Waterstones Piccadilly to sign copies of The Dark Within Them and grabbed a very fancy cake in Soho with a very silly price tag (it was yummy, though).

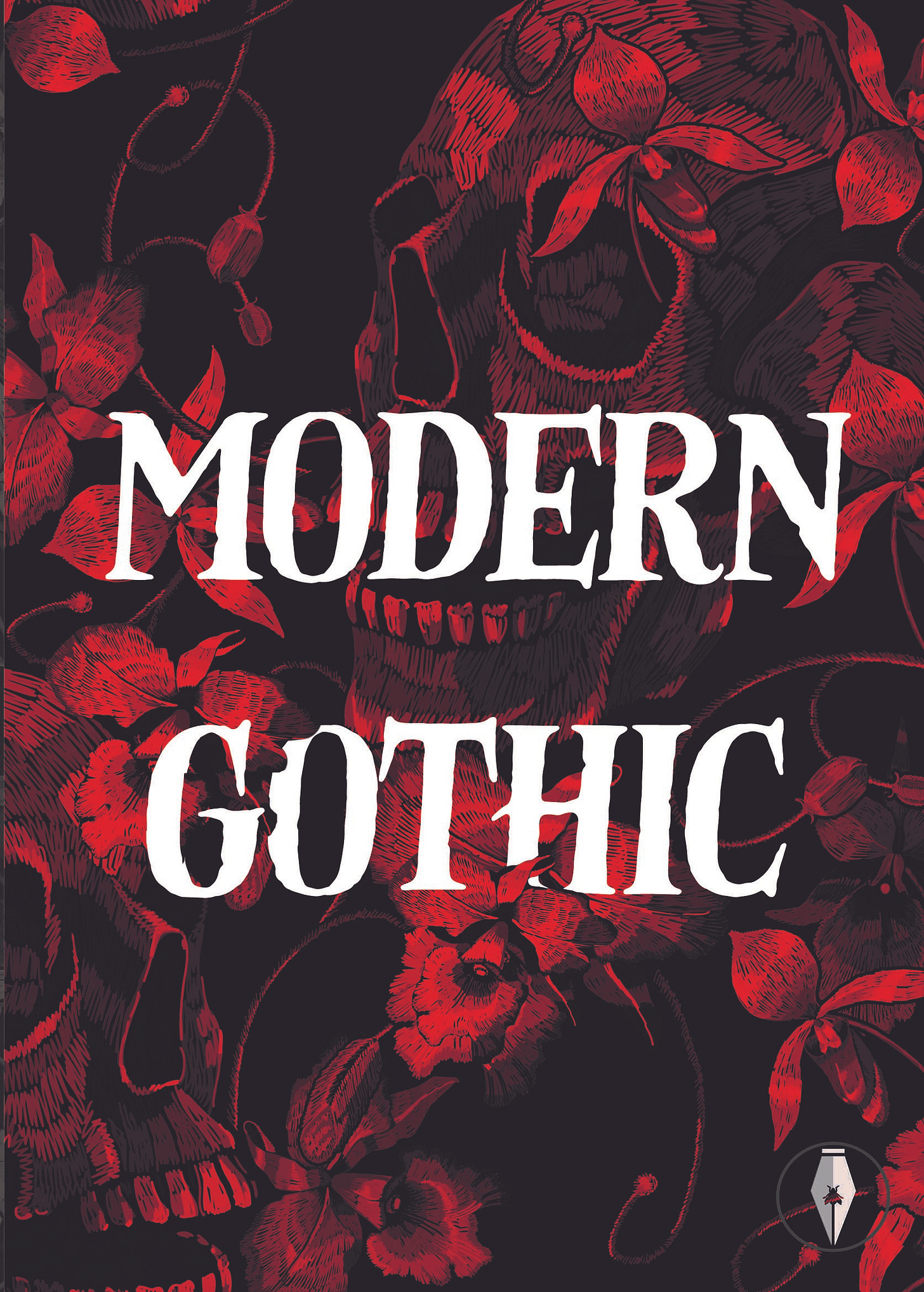

Last year we posted a call out for modern ghoulish tales for our ‘Modern Gothic’ anthology, released on October 11th. In today’s newsletter, we focus on the genre of the gothic, and the short story form.

Embark on a chilling journey through nightmarish tales that will captivate the ghoulish modern reader. Encounter landlords with sinister requests, ethereal housemates, and a glass-encased jungle built by an eccentric father. These gothic stories blur the lines between dreams and reality, weaving a tapestry of macabre encounters and festering secrets.

Introducing ‘Modern Gothic’

We spoke to one of the six short story writers in our upcoming anthology, Michael Bird. His tale ‘A Glasshouse for Esther’ revolves around Herbert Cardew, a wealthy heir who built an enormous 600-acre glass greenhouse filled with exotic plants and animals in an attempt to bond with his daughter Esther. However, for years Cardew has been a recluse, and a journalist investigates to discover the truth behind a long-undisclosed tragedy.

The Gothic genre often explores themes of the supernatural, darkness, and the macabre. How does "A Glass House for Esther" incorporate or subvert these traditional Gothic elements?

‘Esther’ deploys an arsenal of gothic tropes – a large, dark house, a family tragedy, a mysterious death and a disappearance – at the service of a story which aims to critique excessive wealth and colonialism, while also showing how the plunder and disrespect for natural resources can lead to our destruction.

Why use a country house horror for this purpose? I hate country houses. They represent all that is vulgar, abusive, dangerously nostalgic and self-indulgent about British society. Such estates employ a dazzling, but garish form of beauty as a smokescreen to hide the violent methods used to accumulate the riches that paid for the rooms, furnishings and landscaping. At best, they are no more than charming surroundings for a sunday picnic or a pleasant platform for squirrel-watching. However, a large sect of the British populace glorify these kitsch symbols of imperial menace as though they are the supreme cultural achievement of our nation. Boris Johnson said: “If British history had not allowed outrageous financial rewards for a few top people, there would be no Chatsworth, no Longleat.” I would quite happily give up Chatsworth and Longleat if this meant one child didn’t go hungry, and to declare that a pile of bricks cemented into pilasters and porticos and a bit of hedgerow shaped into a maze hold greater importance than a better opportunity for a single human life is a cruel and fetishistic moral position to adopt.

The story features an eccentric and reclusive character in Mr. Herbert Cardew. How did you construct his character - is based on anyone you know?!

Cardew is not based on anyone I know, but I wanted to create a sympathetic main character. He’s an educated, intelligent man, and a good father, who only wants the best for his daughter. As he possesses vast wealth, it seems logical for him to purchase the greatest gift possible for her: the natural world encased in glass, as an annex to her bedroom. He never debates the ethics or morality of this choice, because he doesn’t have to. Mega-wealth gives people the freedom not to have to question their actions.

The glass menagerie at the heart of the story is described in vivid and unsettling detail. Where did this idea of a kind of glass jungle spark from?

The idea came when I was playing Minecraft. In the computer game, you can build huge glass constructions, and fill them with animals, such as sheep, chicken, pigs, horses, ocelots and mooshrooms, a hybrid of a cow and a mushroom. When these animals are trapped in a confined space, they fight, breed and eat each other. There is no limit to how many animals you can spawn in one place. This becomes a digital analogy for the survival of the fittest. I tried to apply this vision to the era of Darwin.

The relationship between Esther and her father is central to the story. How does this dynamic, particularly Esther's fascination with the conservatory's inhabitants, add to the Gothic sensibilities of the tale?

The spine of the story is the relationship between Cardew, Esther and the house, Rackonton. Many of the best Gothic tales centre on family politics, where one key member is a building: Manderley in Rebecca, Thornfield Hall in Jane Eyre, Bly in Turn of the Screw, Eel Marsh House in The Woman in Black. Houses represent isolation, secrets, sexual tension and class anxiety, and the dark corridors, hidden recesses and basements become a symbol of guilt, past crimes, or the subconscious. Rackonton is not a psychological allegory for a state of mind: it’s a character in a cautionary tale about a rich man’s attempt to subjugate a wilderness to the gently sadistic sensibilities of British imperial culture. What’s great about the gothic style is you can mix it with other genres - Du Maurier’s Rebecca is a gothic romance, MR James’s The Ash-Tree is a gothic ghost story, Sarah Walters’s The Little Stranger is a gothic psychodrama. ‘Esther’ attempts to be both a gothic political satire, and a gothic eco-thriller.

The story explores themes of societal propriety and the contrast between the civilized and the savage. Do you feel humans, on the whole, veer towards civilized or savage in our nature?!

One could argue that the Victorian era (in the UK) came to an end in 1914, when supposedly civilised nations engaged in a war that killed a generation of young men. Even before then, British colonial genocides occurred in Ireland and India, so the notion of separating groups of people into ‘civilised’ and ‘savage’ is pointless. ‘Civilisation’ becomes a veneer for impunity. There is a great moment in the 1970s TV series Civilisation, where art historian Kenneth Clark outlines his principles for a civilised society: “order, creation, gentleness, forgiveness, knowledge, human sympathy [and the belief that] all living things are our brothers and sisters”. This is Eurocentric, patrician and a little patronising, but these qualities are pretty inarguable. His perspective shows the real tragedy is always the gulf between human ideals and the implementation of these ideals. When Clark’s list of qualities are not practised at every level of society, this is where savagery thrives.

The use of first-person narration from the perspective of the journalist adds an air of mystery and uncertainty to the story. How does this narrative technique enhance the Gothic elements of the tale?

A journalist interviewing the protagonist adds a framing device, which puts the main character into context (Ann Rice used something similar in Interview with the Vampire). But it also suggests the narration may be unreliable, which is a major element of gothic fiction, especially in, say, Wuthering Heights. Such a novel is restrained by the narrator, and the reader has to work to set the story free. In this way, the reading process itself becomes an act of liberation for the characters. In ‘Esther’, having a vain, pushy journalist at the heart of the story is a good trick, as he is an individual who can go places and talk to people, and becomes a lens for the reader to understand the events, without the writer having to spell them out. However, the journalist in ‘Esther’ is not very perceptive, and doesn’t realise what’s going on. Hopefully, at the end of the story there is a dramatic irony when the reader figures out what is happening, but the journalist is too blinded by his own prejudice to understand.

What do you hope readers will take away from your story?

The best a writer can ask for is that they can make a reader laugh, cry and provoke shock, and leave them something to think about. I hope the readers enjoy and like the central characters, while at the same time deplore the society they represent, and the decisions they take.

Having read 'Modern Gothic', which of the other tales has kept you up at night the most and why?!

All the stories in the anthology are different, and have great merits - Pete Hartley brings a new take on Victorian mesmerism, Edward Karshner shows a fresh multi-temporal approach to the Appalachian ghost story, Lerah Mae Barcenilla blends Philippine folk tales and modern romance, Lauren Archer builds a captivating freak-show about private renting and Rose Biggin has constructed a 19th century body horror - think Bridgerton meets Saw - which is both disturbing and satirical, and lingers in the mind of any parent who has seen their family’s housing situation put into a precarious state.

Thank you so much for these insights Michael! You can preorder a copy of ‘Modern Gothic’ here.

Take care,

Isabelle